The Five Social Inequities that Urban Planning Contributes to and How to Address Them

A Framework

For a profession that exists to look after the public interest and the common good, Urban Planning can find itself paralyzed in a constant tug of war between dealing with the legacies of past urban status quos and implementing the promise of better futures. Futures, in plural, that are incrementally paved with good intentions like those of their predecessors. These are contested and unguaranteed futures that may sprout a plethora of unforeseen inequities as experienced by many city dwellers today. Is the profession crippled by its own balancing act or is there a stance Urban Planning can take towards making clear which urban matters matter the most? Let’s dive in.

Why Hasn’t Urban Planning Solved All Social Inequities?

I think this is a fair question to ask, after all, didn’t this conversation start in the 1960s already? The short answer is: The profession hasn’t solved all social inequities because it hasn’t assimilated the differences between a) how Urban Planning has contributed to the creation and perpetuation of social inequities, with b) how it continues to contribute and c) how it can address that contribution.

The longer answer can take us to many places. For instance, the Urban Planning profession as a whole might seem like a scapegoat of sorts, a catch-all mechanism, where no culprit can be found accountable. In this case, when speaking about the profession I’m referencing the everyday planning practitioner, not the institutions. You know, the practitioners drafting a plan, report, or a regulation, dealing with a client or a public inquiry, or finding themselves wondering about implementing change in their communities. These are the practitioners who are contributing the most to the creation or perpetuation of urban social inequities, but in a way, they can do the most to counter that.

Others might ask, should Planning be dedicated to solving all social inequities? I agree with the feeling behind that question, one cannot blame Urban Planning for everything that cities are experiencing. However, that is not an excuse for inaction. A better framing could suggest Planning to be dedicated to addressing social inequities experienced in cities instead. After all, is not about drawing one-to-one causations and solutions, but acknowledging the need to address in a comprehensive manner the pool of contributions made by practitioners who have biases and a limited understanding. We only know what we think we know, and that creates blind spots in everyday work.

Urban Planners are constantly navigating a pluralism of ideologies, depending on the city that you work in and if you are in the private or public sector you will encounter different traces of political and cultural inclinations that are indicatives of the current status quo. While navigating these and one’s ideologies, Planners encounter the dilemma of looking after the public interest without confusing it with public opinion. The former might strive to care for the welfare or well-being of the general public and society, the latter might drive decision-making and policy directions to benefit just a few. Not realizing the distinction between the two is just one case in which initiatives or policies with good intentions might go off the rails.

Additionally, Urban Planners might find themselves disengaged or powerless to implement change after working in the intricated structures of bureaucracies and power dynamics that exist in city councils, city administration, real estate associations, and civic organizations. Therefore, planning processes should be carefully curated and designed with multiple points of reflection so that there’s a higher chance to learn and adjust throughout implementation and not at the end of milestones. It’s only when we have control of our work, and not our work controlling us, that we can innovate and shift direction to more equitable outcomes.

So, what can be done? How can we take a stance on the way we work? Well, as you’ve probably guessed at this point there are indeed a lot of people out there currently working on bringing urban social justice through urban planning or other means. However, not everyone has the knowledge or privilege to do so, and in the spirit of making a positive contribution to the profession, I want to share the framework I’ve learned and re-adjusted with you. I believe it can help you too.

An Intent Was Made

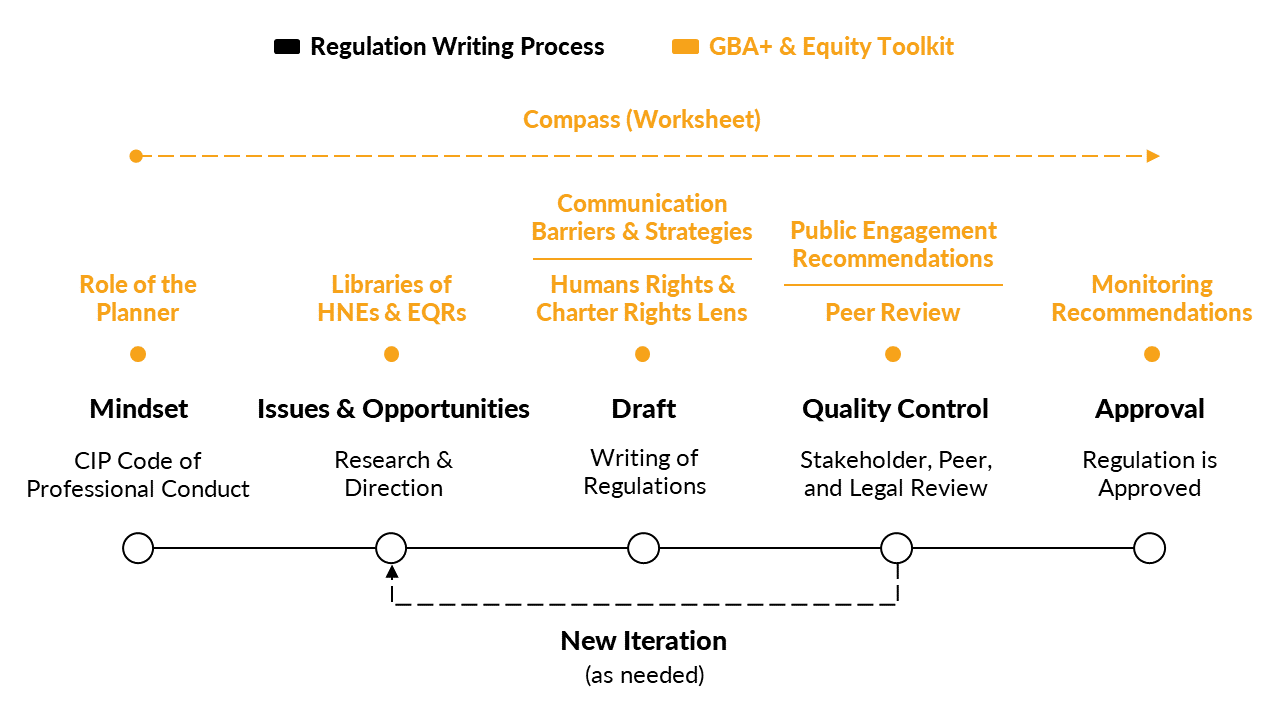

I worked for the last two and a half years on Edmonton’s Zoning Bylaw Renewal, a project striving to overhaul, simplify, and streamline how Edmonton regulates its land use. In 2020, the project was among one of the first pilot projects implementing the Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) framework in the City of Edmonton. This framework was originally created in the 2000s by the Government of Canada’s Women and Gender Equality (WAGE) department and found its way in 2017 through City Council’s motion (CR4189) to provide GBA+ training and implementation to administration. The implementation made its way in 2019 with the release of “The Art of Inclusion”, the City of Edmonton’s diversity and inclusion framework, which would later direct the application of GBA+ across all initiatives prepared by the city.

GBA+ is an analytical tool used to assess the potential impacts of policies, programs, services, and other initiatives on diverse groups of women, men, and people with other gender identities. The "plus" highlights that this type of analysis goes beyond gender and includes the examination of a range of other intersecting identity factors (such as age, sexual orientation, disability, education, language, geography, culture, and income).

The goal of GBA+ is to reduce inequities and ensure equality of outcomes for diverse communities. The framework can be simplified into three concepts: Social Inequities, Identity Factors, and Equity Measures. GBA+ prompts you to research and engage to identify social inequities for your project while considering the intersection of identity factors to prevent groups from being excluded so that you can design, implement, and evaluate equity measures that can address inequities that may impact diverse groups. The challenge was to translate that framework into Urban Planning terms. The result of that exercise was the Zoning Bylaw Renewal GBA+ & Equity Toolkit; an adaptation of the GBA+ method into the planning process of writing regulations. The five social inequities that urban planning contributes to and how to address them come from that experience.

The Five Social Inequities

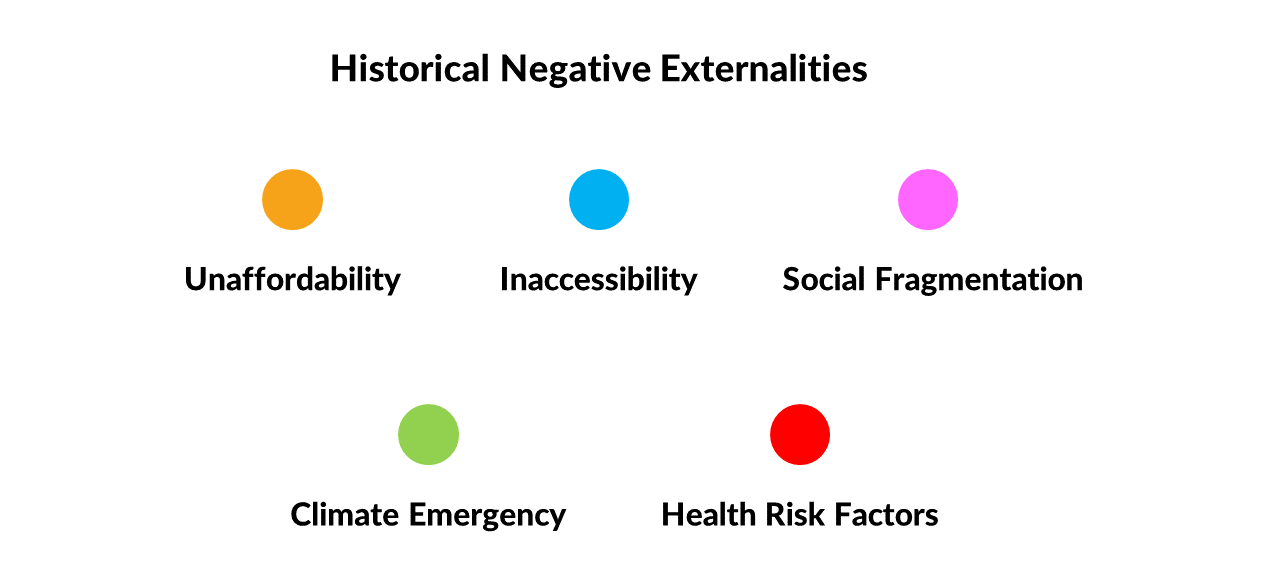

The way we write, design, and implement programs, plans, policies, or regulations can create barriers and impacts over time on vulnerable and marginalized populations. These negative externalities can be both unintentional and intentional and while sometimes unpredictable we can call them historical because we can find records of their impacts in peer-reviewed research, literature, or stories of lived experiences. Historical Negative Externalities or HNEs are the main social inequities that Urban Planning contributes to, and they can be divided into five categories: Unaffordability, Inaccessibility, Social Fragmentation, Climate Emergency, and Health Risk Factors.

The HNE of Unaffordability references the unaffordability of rentals, ownership, and development of real estate in cities.

Examples include:

Decline of Home Ownership • Informal Rental Housing • ‘Roommateships’ • Informal Household Businesses • Houseless Camps • Gentrification/Displacement • Missing Middle

Possible land-use causes include:

Parking Minimums • Restrictive Land Use Regulations in High-Demand or Old Areas • Lack of Diverse Housing Options • Single-Family Zoning • Greenbelts or Protected Natural Areas • Heritage Designations • Direct Control Zones • Complicated Zoning Bylaws • FAR, Setbacks, Height, and Density Restrictions • Low Fire Flow Capacity • High Permit Fees

The HNE of Inaccessibility references the ableism in developments or the lack of access to jobs, civic services, transportation, commerce, amenities, and open spaces.

Examples include:

Disabling Buildings • Disabling Open Spaces • Lack of Civic Services in Old Neighbourhoods • Limitations for Public Facilities and Infrastructure • Lack of Open Spaces in Dense Areas • Lack of Community Amenities in Apartment Buildings • Limited Commercial Business

Possible land-use causes include:

Lack of Accessibility Regulations • Hostile Furniture • Lack of Sidewalks • Physical and Visual Barriers • Restrictive Land Use Regulations in High-Demand or Old Areas • Single-Use Zoning • Lack of Amenity Regulations • Unthoughtful Landscape Regulations

The HNE of Social Fragmentation references perceived insecurity, loss of heritage, and the lack of reconciliation, public engagement, and inclusion in planning processes.

Examples include:

Perceived Insecurity Close to Businesses, Open Spaces, Vacant Lots, etc. • Disrespect of Indigenous Heritage • Lack of Notifications to Renters • Lack of Public Engagement in Private Developments • Oversurveillance • Discriminatory Uses & Definitions

Possible land-use causes:

Redlining • Lack of Public Engagement • Signs Regulations • Single-Use Zoning • Noise Control Regulations • Street Lighting Regulations • Exclusionary Zoning • CPTED • Overregulation

The HNE of Climate Emergency references the development contributions and unpreparedness for future climate change.

Examples include:

Urban Heat Island Effect • Water Contamination • Water Scarcity • GHG emissions • Food Desserts • Loss of Farmlands • Habitat Destruction, Fragmentation, and Degradation • Landfill • Trash Incineration

Possible land-use causes:

Inefficient Land-Use Patterns • Low-Density Zoning • Impermeable Surfaces • Parking Regulations • Urban expansion

The HNE of Health Risk Factors references the development contributions to the aggravation of health risk factors.

Examples include:

Noise • Light Pollution • Air Pollution • Car-Dependency • Weather Hazards • Sun Shadowing

Possible land-use causes:

Lack of Noise Control Regulations • Lack of Light Regulations • Inefficient Land-Use Patterns • Lack of Inclusive Design • Lack of Winter Design • Lack of Public Realm Regulations

Designing Equity Measures

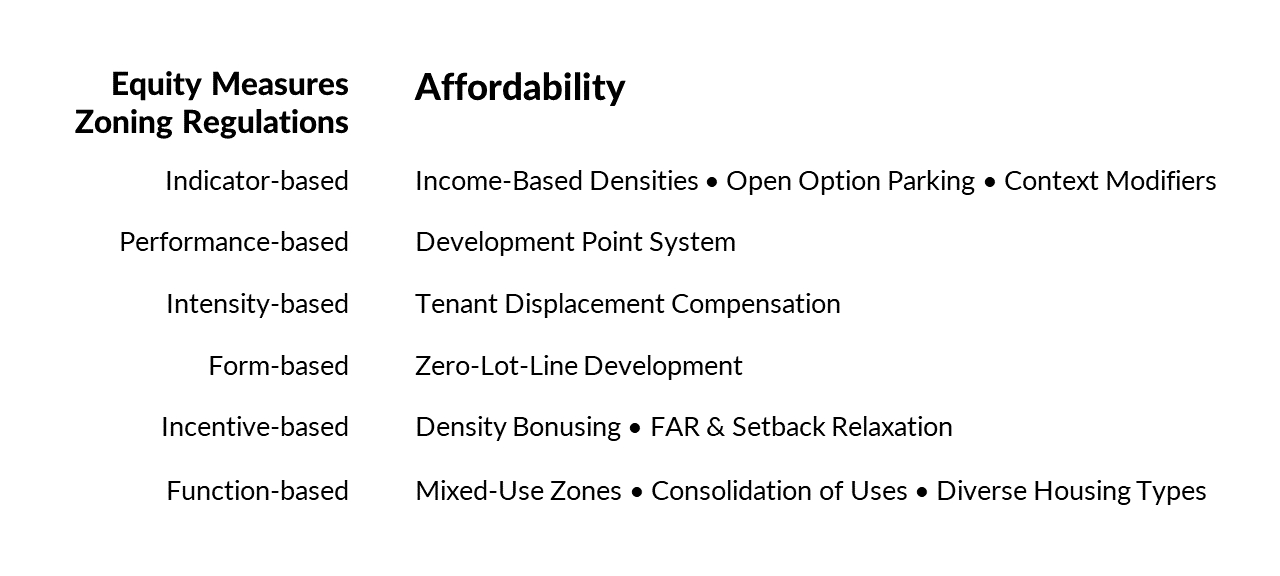

Equity Measures are processes, systems, or actions that remove inequalities or barriers to inclusion and increase equality of outcomes. Not to be confused with Equity Outcomes where these are the aspirational goals we want to achieve through Equity Measures. One can think that affordability is the measure we need to address unaffordability, but that is the goal, not the measure. Equity Measures in Urban Planning can take the form of policies, programs, services, plans, or zoning regulations.

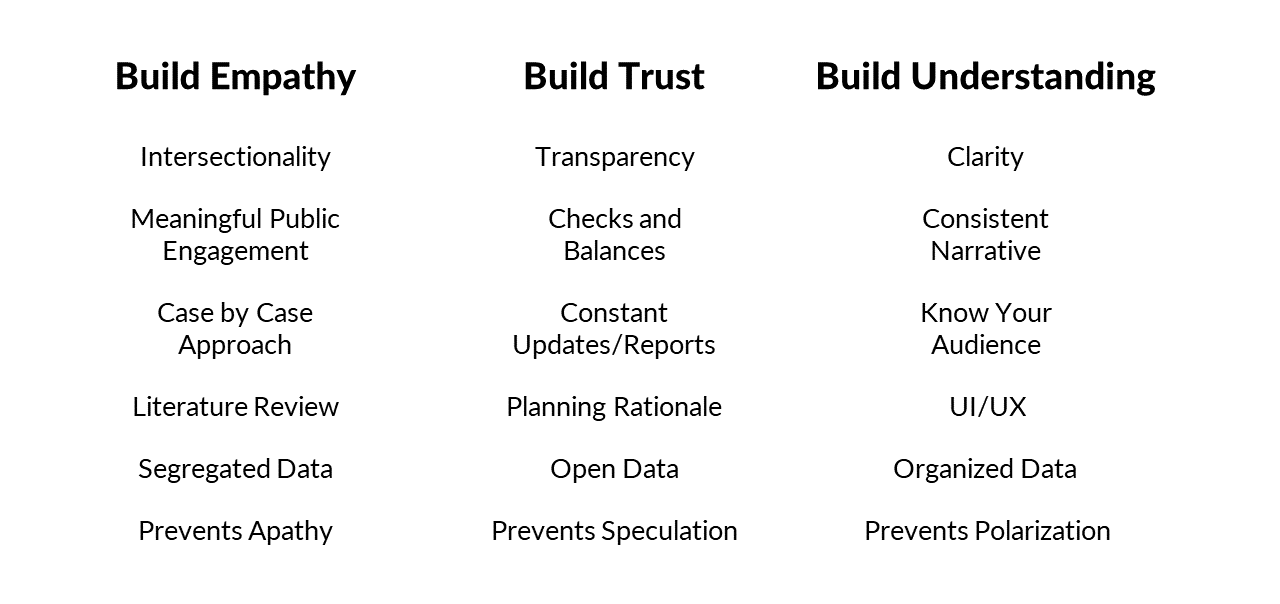

To design Equity Measures there are three principles that come to mind: Build Empathy, Build Trust, and Build Understanding. Building Empathy is about creating the conditions to bring as many perspectives as possible to have a comprehensive, representative and transformational learning experience. Building Trust is about creating the conditions for City Council, stakeholders, and other decision-makers, to validate planners’ recommendations and proposed directions. Building Understanding is not about simplification and minimalization. It's about organization and clarification. It is about seeing relationships. Making the complex clear.

Building Empathy involves having an intersectional lens in the research and analysis stages of the design of a project. This includes having meaningful public engagement (more on this in another post), applying a case-by-case approach to acknowledge as many lived experiences as possible, doing comprehensive literature reviews, and having data that can be easily segregated in multiple identity factors. Building empathy helps prevent the sprout of apathy in a planning process.

Building Trust involves being transparent throughout the process of decision-making that comes while designing the equity measure. Transparency is sometimes the strongest quality a project can have. This includes setting checks and balances, constants updates/reports, writing truthful and well-funded planning rationales, and having data that is open for anyone to analyze and provide their own conclusions. Building trust helps prevent the sprout of speculation in a planning process.

Building Understanding involves having clear communication across the project. This includes having a consistent narrative, knowing your audiences, implementing a User Interface and User Experience approach on how equity measures are presented, and having data that is organized through visualizations, diagrams, illustrations, or maps that can help others connect the dots. Building understanding helps prevent the sprout of polarization in a planning process.

No Silver Bullet

This multidimensional approach implies that there is no one silver bullet in terms of a policy or regulation that can solve one or all inequities. For instance, when thinking about addressing unaffordability there are a variety of regulations and economic indicators that could help reduce the cost of construction, promote mixed-income developments, protect tenants from displacements, use the available space on a site more efficiently, promote diverse housing types, or more mixed-use zones that Urban Planners could recommend.

The right mix of solutions will come from the engagement of building empathy to learn about current needs and lived experiences, from the act of building trust to justify innovations and tough decisions, and from the effort of building understanding to communicate clearly to multiple audiences.

Whichever solutions come out of the process they are not going to guarantee fully the aspired outcomes. That’s why is so essential to know how to monitor policies and make amendments as needed, but that is a post for another day.